2025-04-06_22-01-42

In the 950s AD, during the Later Zhou dynasty in China, Chai Rong—the second emperor—proclaimed:

「雨過天晴雲破処」

“After the rain, where the clouds part and the sky clears.”

What he sought was a ceramic that captured the hue of the sky glimpsed through the breaks in the clouds after rainfall.

Indeed, the color seen through torn, leaden skies is solemn and majestic. Perhaps a beautiful blue reveals its true brilliance only when paired with a color worthy of its contrast.

I, too, possess a blue that I can hold in my hand.

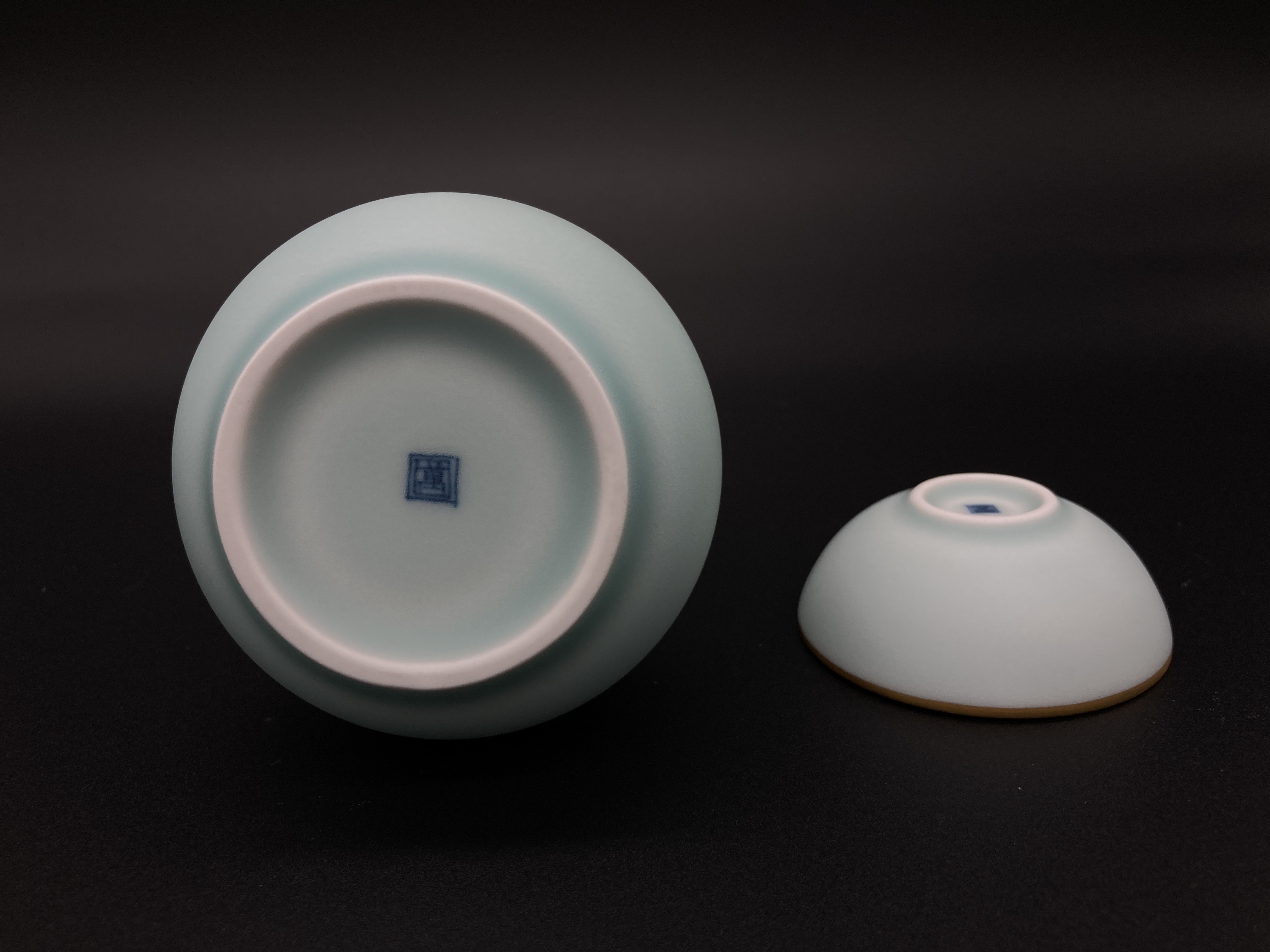

They are two sake vessels made by HATAMAN—celadon ware from Imari.

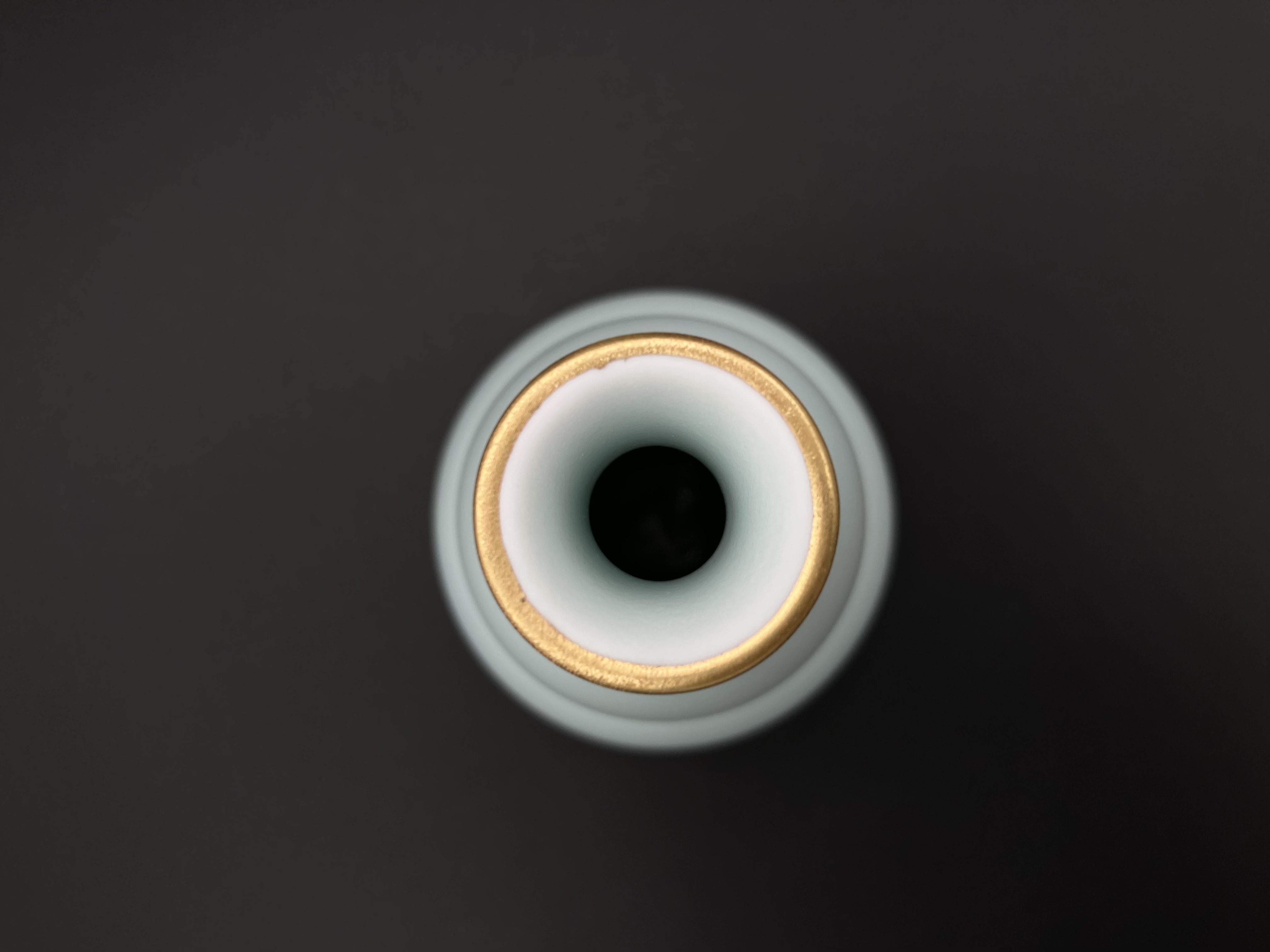

The moist, glassy surface of the celadon is so soft and pale, it seems ready to dissolve into space itself. Yet a band of gold holds it firmly in place. I had long understood that blue can define the edges of blue, like the sky meeting the sea on a clear day. But this particular blue was one I had never known before (良く晴れた海辺の空の様に,青は青の境界となりうることを知ってはいたが,この青はまだ私の知らない青だった).

I found myself wanting to carry this sky with me always. I tried photographing it using studio lighting. However, the images failed to capture the color my eyes perceived. The blue could not be anchored by the gold band alone. Even after adjusting the lighting and camera settings, it remained elusive.

Eventually, I placed the celadon piece on my desk beside a window, where the outside scenery was visible, and turned to other work.

Then, quite unexpectedly, I saw it—the blue reflected from the celadon surface, touched gently by natural light. I took the photo just as it was, and at last, the color as I had seen it was faithfully preserved. Perhaps it is because natural sunlight contains a broader spectrum of wavelengths than artificial LED light.

True to my scholarly habit, I turned to the literature to learn more about the blue of celadon.

It is said that this blue arises from cobalt ions within the glaze. Impurities—such as iron, manganese, and nickel—introduce rich variations in tone. These glazes are believed to have arrived from China and Korea around the 1600s, during Japan’s Azuchi-Momoyama period, and later became a major export to Europe during the Edo era.

A study of early 17th-century Imari ware reveals the following:

- The blue consists of a matrix scattered with needle-like crystals and spherical microparticles.

- The needle-shaped crystals are amino-silica-based and contain silicon, aluminum, calcium, and oxygen.

- The coloration originates from amorphous, cobalt-bearing spherical microparticles.

The study notes that further detailed analysis will require firing experiments using samples of known composition.

Modern science may stand in awe of celadon's complex composition and microstructure. But beyond that, one cannot help but feel a sense of wonder—perhaps even reverence—for the history and craftsmanship woven into each vessel.

I invite you—go to Imari.And there, hold in your hands the sky, captured in celadon.

https://hataman.jp/

https://doi.org/10.2320/jinstmet.72.483